A few miles southwest of Sulaymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan, the French archaeological mission of Piramagrun has been excavating the site of Kunara since 2012. The unearthed city, dating back to the third millennium BCE, was revealed to have unique characteristics and a shroud of mystery around its founding people..

Site of Kunara reveals archaeological remains

of a thousands-year-old city at base

of Zagros Mountains

The Kunara archaeological excavation project started in 2010. Brought to a stop since the 1990 American embargo, the Kurdish authorities wanted to rekindle archaeological interest in the region. To achieve that, they got in contact with foreign archaeologists who excelled in this field including French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) Research Director Christine Kepinski known for her excavation of the Middle Euphrates Valley during the 1980’s. This is how Christine Kepinski flew to Kurdistan to evaluate the possibility of an archaeological mission in the region. She was assisted by Aline Tenu, who was destined to take over the project after Christine Kepinski’s retirement.

The Kunara archaeological excavation project started in 2010. Brought to a stop since the 1990 American embargo, the Kurdish authorities wanted to rekindle archaeological interest in the region. To achieve that, they got in contact with foreign archaeologists who excelled in this field including French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) Research Director Christine Kepinski known for her excavation of the Middle Euphrates Valley during the 1980’s. This is how Christine Kepinski flew to Kurdistan to evaluate the possibility of an archaeological mission in the region. She was assisted by Aline Tenu, who was destined to take over the project after Christine Kepinski’s retirement.

After discussions with the Director of Sulaymaniyah Antiquities, the two women decided to build a dossier in order to carry out a mission on the site of Kunara. That location offers several advantages: its presumed scientific interest is great and its proximity with Sulaymaniyah makes it easily accessible. The project was approved by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs in 2011 and it began the following year.

A strange city

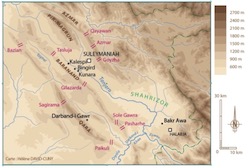

Kunara lies at the base of the Zagros Mountains, in northwestern Mesopotamia and its famous five millennia old cities. Despite the region’s relief, ancient human settlements are relatively easy to identify because they appear in the shape of tells. Tells are artificial mounds created by the repeated destruction and construction of buildings one on top of the other. These ultimate marks of the history of ancient cities allow archaeologists to know where to excavate.

Kunara lies at the base of the Zagros Mountains, in northwestern Mesopotamia and its famous five millennia old cities. Despite the region’s relief, ancient human settlements are relatively easy to identify because they appear in the shape of tells. Tells are artificial mounds created by the repeated destruction and construction of buildings one on top of the other. These ultimate marks of the history of ancient cities allow archaeologists to know where to excavate.

The tell’s size gives a rough idea of the city’s surface area which, in the case of Kunara, would be a little under 25 acres. Even though it does not even come close to Babylon’s 2,411 acres under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II 1,500 years later, the site will still reveal a huge archaeological potential and numerous surprises.

The first being the size of the buildings: right from the start of the excavation of the upper town, the crew discovered a monumental structure including a courtyard spanning a minimum of a thousand square feet. Such dimensions suggest that it was a public building. However its precise use remains uncertain although the voluntary filling of the construction – a known practice – may suggest a desecrated temple.

More surprising still, other monumental structures are uncovered elsewhere on the site, especially in places supposed to be part of the lower city. In Mesopotamian cities, the lower part of the cities usually only hold domestic dwellings. Kunara differs in that aspect, since it does not seem to be built following the Mesopotamian model.

More surprising still, other monumental structures are uncovered elsewhere on the site, especially in places supposed to be part of the lower city. In Mesopotamian cities, the lower part of the cities usually only hold domestic dwellings. Kunara differs in that aspect, since it does not seem to be built following the Mesopotamian model.

The archaeologists also noticed some differences in the construction techniques: while Mesopotamian cities are built using raw bricks, the construction method in Kunara looks like it uses cob or the rammed earth – or pisé – technique. This other particularity made the identification of the walls much harder when starting the excavation.

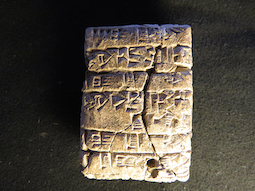

All of this intrigued the crew, especially since other elements indicated a strong Mesopotamian cultural influence, starting with the ceramics or the many clay tablets found on site. These were written in Akkadian using Sumerograms, meaning cuneiform characters forming Sumerian words. It is true that Akkadian is not linguistically related to Sumerian, which is a language isolate, however Akkadian still borrows many Sumerian terms that can be found in written texts.

Questions and hypotheses

What do we know, or assume we know, about this city’s inhabitants? The preferred hypothesis is that the builders of this city were the Lullubi people, of whom we don’t know much. Kunara could even be the capital city of their kingdom: Lullubum. No one knows the language spoken by the Lullubi. In the discovered tablets, certain names or places don’t seem to have any link with either Akkadian or Sumerian. It could very well be a totally different language.

What do we know, or assume we know, about this city’s inhabitants? The preferred hypothesis is that the builders of this city were the Lullubi people, of whom we don’t know much. Kunara could even be the capital city of their kingdom: Lullubum. No one knows the language spoken by the Lullubi. In the discovered tablets, certain names or places don’t seem to have any link with either Akkadian or Sumerian. It could very well be a totally different language.

Everything points to Kunara being a significant trade center as well as a relatively wealthy city. Ancient rare animal remains (lions, panthers, horses, etc.), probably worthy diplomatic gifts, are evidence for that. Despite the lack of mineral deposits around, the discovery of lithic tools made of obsidian reinforces that theory. It is quite surprising for that matter that rare materials were used to make day-to-day tools, like observed on the site.

Everything points to Kunara being a significant trade center as well as a relatively wealthy city. Ancient rare animal remains (lions, panthers, horses, etc.), probably worthy diplomatic gifts, are evidence for that. Despite the lack of mineral deposits around, the discovery of lithic tools made of obsidian reinforces that theory. It is quite surprising for that matter that rare materials were used to make day-to-day tools, like observed on the site.

The city likely owed its prosperity to its agricultural resources: among the buildings identified with certainty, the archaeologists have unearthed a “flour office”, an important administrative building in which flour from the region was collected and weighed. Among the accounting tablets found in another “flour office” is a term that was never encountered before: the gur of Subartu. In the region, the gur was an important measurement of volume, generally linked to the imperial gur of Akkad. However the term Subartu (the north, in a broad sense) led the archaeologists to think that there needed to be a distinction between this measurement and the imperial gur and therefore strong links with the Akkadian Empire. Were they trading with Akkad or subjugated by it?

In addition, no outer wall was uncovered despite the size of the city. Would Kunara be more extended than initially thought? Would the city walls be located in a yet to be explored area? Could a sizable trade center such as Kunara simply lack such walls? As of today, all these questions remain unanswered by archaeologists. The very name of the city is still a mystery as Kunara is its modern name.

The end of Kunara

All of these constructions were abandoned around 2100 BCE. Traces of a fire dating from that period can be found all around the city, clearly indicating the cause of the city’s fall. However, was it accidental or voluntary? While the cause of the fire remains unclear, the sheer size of it would give credit to the military destruction thesis.

All of these constructions were abandoned around 2100 BCE. Traces of a fire dating from that period can be found all around the city, clearly indicating the cause of the city’s fall. However, was it accidental or voluntary? While the cause of the fire remains unclear, the sheer size of it would give credit to the military destruction thesis.

If that is the case, we can naturally ask ourselves this question: by whom? Again, several hypotheses are possible: a local conflict with the neighboring city which lays 15 miles away, a regional war with another kingdom of Zagros, or maybe a total destruction by the hand of one of Akkad’s kings or of the Third Dynasty of Ur, known for having led military campaigns in the region at the time. Besides, the war-mongering king Shulgi boasted to have destroyed Lullubum nine times. This hypothesis is thus appealing.

What next for the excavation site of Kunara?

There is still much to learn in Kunara. However, for the second consecutive year after the first hiatus caused by Covid, work on the site won’t resume in 2021. In fact, the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs knocked the region down from orange to red (strongly discouraged). Even if an ad-hoc authorization could still be delivered, it would come too late for the mission to resume, putting the oh-so-wished-for answers on the backburner for the foreseeable future.

Sources

- Interview by Aline Tenu, July 1, 2021 – Lionel Tabourier, “Archaeological excavation in Kurdistan. Interview with Aline Tenu”, November 30, 2021 [In French only]

- Jean-Baptiste Veyrieras, “A Historical Treasure Bordering Ancient Mesopotamia”, CNRS, le journal, March 18, 2019 [English & French versions available] https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/a-historical-treasure-bordering-ancient-mesopotamia

Learn more

- Visit the Piramagrun archaeological mission website to access field reports and more.

- Vincent Charpentier, [In French only] “Archaeology of Iraqi Kurdistan”, France Culture – Carbone 14, le magazine de l’archéologie, March 31, 2019

- Visit Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia to learn more about these subjects: Mesopotamia, Euphrates, Zagros Mountains, Akkadian and Sumerian.

Would you like us to do an interview, a book or documentary review, or another review relating to archaeology, whether for the general public, for children or for specialists? Write to us thanks to our form.

ArkeoTopia, an alternative approach to archaeology® aims to take a fresh look at the archaeology of today to contribute to preparing for the archaeology of tomorrow. To learn more about us, feel free to check out our institutional video and our activities.