By experimenting with the biological sex and the symbolic sex of animals, our ancestors left for us evidence of their high level of abstraction and their understanding of the world, more complex than we had previously imagined. iconography of the Near East tells us about the complex thinking of Bronze Age Syrians.

Interactions of Biological Sex and Symbolic Sex:

Complex Worldviews during Antiquity

From the Paleolithic to today, if all or part of an image can provide information about the culture that created it and when, could it also provide other information? Can full or partial images give an account that clearly explains what is depicted but also why it is depicted and, going further, teach us about the culture that created it? Today, images can do all of this, thanks to “the iconogenetic method.” The various characteristics that will reveal the specificities of each element of the image must be gathered to establish the iconographic genetic sequence, like DNA. The image can then tell us quite a bit about the craftspeople and artists who created it.

From the Paleolithic to today, if all or part of an image can provide information about the culture that created it and when, could it also provide other information? Can full or partial images give an account that clearly explains what is depicted but also why it is depicted and, going further, teach us about the culture that created it? Today, images can do all of this, thanks to “the iconogenetic method.” The various characteristics that will reveal the specificities of each element of the image must be gathered to establish the iconographic genetic sequence, like DNA. The image can then tell us quite a bit about the craftspeople and artists who created it.

Example: representations of bovines and felines from the Syrian Bronze Age – 3rd-2nd millennia BCE

![]() The first challenge faced by iconologists – scientists who study images – is managing to identify the representation to be studied. How can they know if it depicts a human being, or an animal, or something else entirely?

The first challenge faced by iconologists – scientists who study images – is managing to identify the representation to be studied. How can they know if it depicts a human being, or an animal, or something else entirely?

This is only possible after establishing criteria through discussions between the iconologist and other specialists. For the field of animal iconology, specialists include those who work with animals, such as zoologists, ethologists, paleozoologists and archaeozoologists, as well as breeders, veterinarians and zootechnicians.

Using this method, which I named the iconogenetic method, specialists can define precise criteria that are open to evaluation. These criteria are alone in being able to provide a proven identification that can be further developed by other iconologists. This method makes it possible to correct identifications already made in the past. This is how it was determined that artists during the Bronze Age in Syria produced more asexual (60%) than sexual representations, with only 35% depicting male cattle and 4% female cattle.

Towards new knowledge

In addition to these quantitative results, the reassessment of identifications revealed associations that had previously gone unnoticed. Why would a Bronze Age craftsperson, who knows how to represent an animal naturalistically, go and make this representation unintelligible? Today, as the question of gender in our societies brings out diversified associations beyond the binary, it is interesting to note that we were not the first who wanted to display a variety of possibilities.

The representations of Ishtar, Anat and Astarte provide good examples of this. These three goddesses, who are actually one and the same but with certain nuances, offer a symbolism that attests to a complex understanding of the world. As goddesses of love and war, they are typically represented with emblems characteristic of male symbols: horned tiaras, wild animals and weapons.

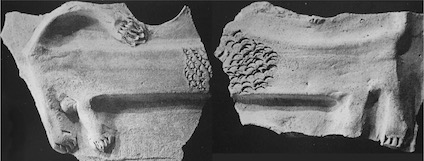

The cylinder seal from Ugarit (first picture), dated to the 14th century BCE, and the terracotta fragments from the Temple of Astarte at Emar (below), dated to the 16th to 12th century BCE, demonstrate this complexity. On the cylinder seal, the goddess, recognizable by her horned tiara, sits on a male bovine and a male lion. This same male lion, with a female lion, serves to support another figure. On the terracotta fragments from Emar, the animals are recognizable as male lions by their manes but have very different genitalia: one has testicles while the other has a vulva. The question then arises as to whether the idea was to represent two male lions with both feminine and masculine symbolism, or one male lion and one female lion with masculine attributes.

This sexual ambiguity is found in the texts about the male Ishtar and the female Ishtar. The association of bovines with male divinities and felines with female divinities is challenged by the association of goddesses (Ishtar or Anat) with both bovines and felines. Numerous artifacts attest to this association, both directly (cylinder seals, the Investiture painting, models, etc.) and indirectly (artifacts showing felines and bovines in the temple of Ishtar) in Mari and in Ebla (stele of Ebla).

However, this ambiguity is not unique to Bronze Age Syria. It is also found in Iraq, with the Khafajah figurine, dated to 2400 BCE, which was discovered inside the altar on the site of Nintu Temple VI. Without an iconogenetic approach and according to a long-prevailing consensus, this figurine was said to depict a male bovine. It is true that the horned tiara and the beard typically correspond to attributes given to representations of the male sex. However, in this case, the presence of udders shows that the craftsperson wished to give their work another dimension. Is it a female bovine with masculine attributes, a male bovine with feminine attributes or possibly a genderless being whose purpose is to combine male and female attributes to illustrate a whole?

Beyond a binary thinking of the world

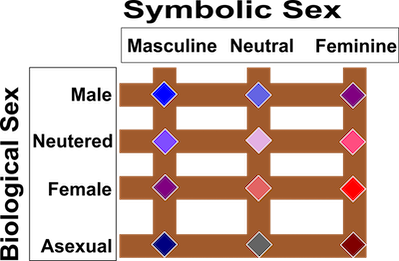

As it stands, the question remains, but it highlights an interplay of biological sex and symbolic sex whose interactions go beyond a simple dual representation of the world to fit into a scheme where:

As it stands, the question remains, but it highlights an interplay of biological sex and symbolic sex whose interactions go beyond a simple dual representation of the world to fit into a scheme where:

- there is a dissociation between biological sex, with its male, neutered and female representations, and symbolic sex, with its male, neutral, and feminine representations;

- the notion of asexuality appears, meaning neither male, nor castrated, nor female; or

- there is a combination of each of these in different aspects, giving a specific meaning to the representation, which may or may not go beyond aesthetic or naturalistic criteria.

This sexual ambiguity highlights the interaction between the biological and symbolic natures of the sexes. This interaction requires the notion that an asexual representation has a significance that biologically exceeds the representation of a being defined by its characteristics or its genitalia. Refraining to assign a sex to a representation is therefore a voluntary choice to see the representation as that of an ideal entity that combines all male and female qualities in a symbolic portrayal that must be defined for each representation.

This iconography thus reveals the complex thought of not only the Syrian culture during the Bronze Age, but potentially of all those of the Middle East at the time. By experimenting with the biological sex and the symbolic sex of animals, these civilizations left for us evidence of their high level of abstraction and their understanding of the world, more complex than we had previously imagined.

Learn more

- Gransard-Desmond J.-O., Animal iconology: Identifying animal representations to aid archaeological analysis, communication to the 22th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists, Vilnius, 2016.

- Gransard-Desmond J.-O., Étude sur les Canidae des temps pré-pharaoniques en Égypte et au Soudan, British Archaeological Reports – International Series 1260, Oxford: Archaeopress, 2004.

- Thomas Mitchell W.J., Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Iconology, in: Wikipedia, [Consulted on November, 30, 2022].

This article was published during the 2020 edition of France’s Science Festival (Fête de la science), from October 2 to 12, 2020 in mainland France and from November 6 to 16 in Corsica, overseas territories and internationally. The Conversation France is a partner of the festival. The theme of the 2020 edition was “Planet Nature”. Find all the events in your region on the official site: fetedelascience.fr.

Would you like us to do an interview, a book or documentary review, or another type of review relating to archaeology, whether for the general public, for children or for specialists? Write to us using the ArkeoTopia contact form.

ArkeoTopia, an alternative approach to archaeology® aims to take a fresh look at the archaeology of today to participate and to better help existing organizations prepare for the archaeology of tomorrow. To learn more about ArkeoTopia, check out our institutional video and our activities.